Poisson Point Processes

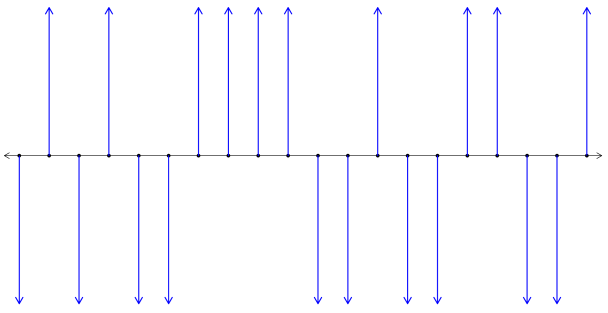

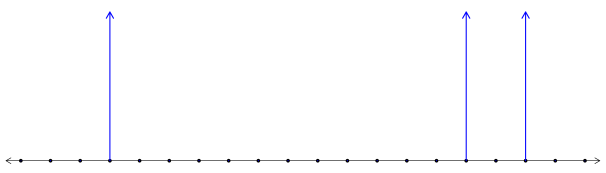

Recall a realization of the basic noise for Gaussian processes looked like that in Figure 1. Now, arrows are either muted or (rarely) point up. See Figure 2.

1 Motivation

Suppose in some space we lay down a large number of LED lights, each with their own battery, with density given by a -finite measure . We do this in a way so that, for each region , we put down about lights in that region, where is some large number. Independently we turn on each light with probability , and leave off otherwise.

We would like to answer the following question: how many lights in are on? To that end, let denote the number of lights on in and compute

| (1) |

Thus gives the expected density for the set of lights that are on in . By construction, we know , and hence the distribution of is approximately . To see this, put and observe,

| (2) | ||||

| (3) | ||||

| (4) | ||||

| (5) |

This motivates the following definition. {definition} Let be a -finite measure on some space . A Poisson Point Process (PPP) on with mean measure (or, intensity) is a random point measure such that:

-

1.

For any Borel set , we have and , i.e.

(6) -

2.

If and are disjoint Borel subsets of , then and are independent random variables.

Recall a point measure is just a measure whose mass is atomic. That is, if then a point measure is of the form

| (7) |

where is the unit point mass at .

2 PPP Properties

It is sometimes useful to think of a PPP as a random collection of points. With this in mind, we list some important properties of on some space :

-

•

Enumeration: It is always possible to enumerate the points of , i.e. there is a random collection of points such that

(8) -

•

Mean measure: If then

(9) Note: This is a more general property of point processes, as any point process has a mean measure. To see (9) holds without needing to be a Poisson point process, let be a simple function, i.e.

(10) Then we compute

(11) This can then be extended to arbitrary measurable functions through the standard limiting procedure.

-

•

Thinning: Independently discard each point of with probability for a point at . The result is a , where

(12) In other words, if and with probability and otherwise, then

(13) -

•

Additivity: If and are independent on , then . In particular, if and are independent, then

(14) -

•

Labeling: For each point in a PPP, associate an independent label from a space according to some probability distribution . Let for and let be iid with density . Then

(15) on .

3 Examples

Henceforth, let denote Lebesgue measure. {example} Let on , where is Lebesgue measure. As before, we think of the points of as ‘lights’, here positioned on the positive reals.

-

1.

How far until the first light?

-

2.

Suppose each light is independently either red or green with probability . How far until the first red light?

Solution.

Let and put . Using (6) we compute

| (16) |

This solves part (a). For the colorblind readers, this also solves part (b).

Now let be the (random) set of red lights and define , the point process for the red lights from . By the thinning property (12), . Similarly define and observe

| (17) |

thus (b) is solved. ∎

Rain falls for 10 minutes on a large patio at a rate of drops per minute per square meter. Each drop splatters to a random radius that has an Exponential distribution, with mean 1cm, independently of the other drops. Assume the drops are 1mm thick and the set of locations of the raindrops is a PPP.

-

1.

What is the mean and variance of the total amount of water falling on a square with area ?

-

2.

A very small ant is running around the patio. See Figure 3. What is the chance the ant gets hit?

Solution.

Let where is the center of the th drop. Take and let denote the number of drops in , so that . Then the total volume is

| (18) |

where is the radius of the th drop. Note this is a sum of random variables where the number of terms is also a random variable. Thus we use Wald’s equation (28) to obtain

| (19) |

The second step in (19) was obtained from the fact that an exponentially distributed random variable with mean has higher moments given by

| (20) |

This is proved by an iterated application of integration by parts, and the result gives rise to

| (21) |

The case will turn out to be useful when computing the variance of .

Indeed, to compute the variance we utilize the variance decomposition formula. Observe,

| (22) | ||||

| (23) | ||||

| (24) | ||||

| (25) |

This solves part (a).

Now, part (b) can be solved by way of the labeling property. Here, we use the radius of the th drop to label the point . Recall the density of an Exponential random variable with mean is . So we define a measure on by

| (26) |

We think of as the (closed) upper half plane in where the third coordinate is a realization of . By the labeling property (15), on . For the ant to remain dry, any drop with radius must land outside the circle of radius centered at the ant. Viewed from the space , we want to integrate over the cone with its tip at the ant, whose horizontal cross-section at height is a circle of radius . From this we compute

| (27) |

Plugging in the given value for yields . The ant had better grab an umbrella! ∎

3.1 Wald’s Equation

The following is the statement of Wald’s equation, taken from Wikipedia11 1 The proof is also on Wikipedia.. {theorem}[Wald’s Equation] Let be a sequence of real-valued, independent and identically distributed random variables and let be a nonnegative integer-valued random variable that is independent of the sequence . Suppose that and the have finite expectations. Then

| (28) |